Northern Neighbors of the Norsemen - the Sámi

2021-07-09

What we know about the medieval Sámi

- relations with the Norse

- reputation among the Norse

- and why the sources are the way they are

The Sámi are the only indigenous peoples of the European Union. The territory they inhabit, known as Sápmi, extends beyond the EU’s borders, from Norway to Western Russia. The modern Sámi are the descendants of nomadic hunter-gatherers who inhabited Fennoscandia prior to the arrival of Germanic and Finnic groups from the south. In the Viking Age, of all the Norse neighbours the Sámi – whom they called Finnar – were the most prominent. Medieval sources describe the Sámi engaged in both trading and tributary relations with the Norse, as well as portraying them as a pagan people who traded in highly desirable goods and were exceedingly skilled in hunting, skiing, and magic. While explicitly Christian sources attribute various evils to Sámi magic, there is generally an air of fearful respect of the Sámi capabilities.

Viking Age and later medieval sources mentioning the Sámi include the kings’ sagas of Icelander Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla, some of the Sagas of Icelanders, including Egils saga and Vatnsdæla saga, as well as the account of chieftain Ohthere’s voyages found in the so-called Old English Orosius believed to originate at King Alfred the Great’s court. The Norse relationship with the Sámi seems to have begun as a fairly normal trade relationship, with the Norse, for whom farming was the most important source of livelihood, trading with the nomadic hunter-gatherer Sámi to acquire desirable northern trade-goods such as furs, feathers, reindeer, walrus ivory, whalebones and seal- and walrus-skin ropes. However, this relationship would not last, particularly after Norse society began organizing, expanding settlement northward and projecting military might against their neighbours. As Norse polities headed by regional chieftains formed, these relationships became more tributary in nature. In the late tenth century Ohthere the Hålogalander chieftain claimed that the Sámi tributes were his main sources of wealth. According to Ohthere the Sámi tributes depended on the rank of the individual being taxed, with the highest taxes including numerous skins from martens, reindeers and bears, feathers, fur-tunics, as well as ship-ropes made from seal- and walrus-skins. Based on these sources we can see that already in the tenth century, the Sámi-Norse relationship was far from equal.

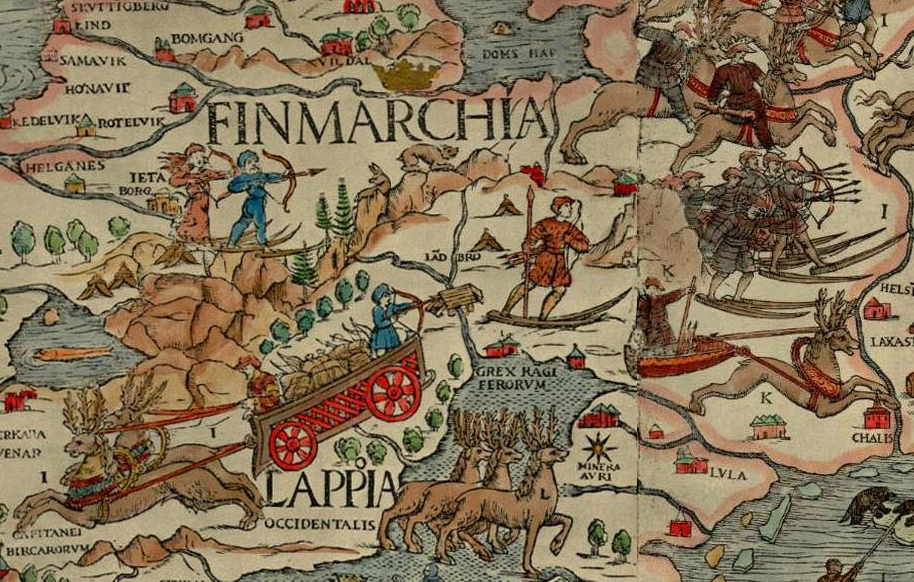

A detail from 16th century Swedish cartographer Olaus Magnus' Carta marina depicting Sámi skiiers below the Latin label Finmarchia, which corresponds to the Old Norse Finnmörk.

This same tributary relationship is also recorded in both the kings’ sagas as well as the Sagas of Icelanders written mainly in the thirteenth century, though by then a shift had occurred in the relationship – rather than paying tribute to regional chieftains, the Sámi tribute was paid to the kings of Norway, whose officials would journey throughout the North collecting the king’s taxes. In Egils saga Egil’s uncle Þórólfr Kveldúlfsson served for a period as king Harald Fairhair’s steward in the mountainous regions of northern Norway, with royal permission to trade with the Sámi. Access to the highly profitable trade-goods provided by the Sámi was restricted to the king and his agents, who according to the sagas were able to trade at very favourable rates of exchange. The king and his men also defended this privilege, with Egils saga including a scene in which Þórólfr hunts down and kills a group of men who had traded with the Sámi without permission. It is in fact likely that the Norse began expanding into the borderlands inhabited by the Sámi – the Finnmörk as it is called in the sagas – because control of the trade-goods of the Sámi was so profitable to the Norse.

Apart from the depiction of the material value the Sámi provided to their neighbours, the sagas have much to tell of the supernatural associations of the Sámi. It appears to have been a common belief held by the Norse that the Sámi were descended from giants and trolls. For example Ketils saga hængs includes a half-Sámi character called Hallbjörn Halftroll, and in the Icelandic Landnámabók – the Book of Settlement – one Hrafsi Ljótólfsson is described as being descended from risar – giants. This supernatural lineage is used as an explanation for the magical abilities of the Sámi in many Norse legends. King Harald Fairhair is bewitched by the beautiful Sámi woman Snæfriðr, whom he marries and dotes on day and night, neglecting the rule of his kingdom, even lying by her dead but undecayed body for three years after her death; Erik Bloodaxe’s wife Gunnhildr is reported as having studied magic under the tutelage of two Sámi wizards in Finnmörk; Ingimundr, an early settler of Iceland, is aided by a pair of Sámi wizards in locating the site of his future farmstead on the recently discovered island. The Sámi magic is often described as sinister and dangerous in sources written by Christian authors and particularly in royal legends, but helpful in legends with ‘folksier’ protagonists. The Norse also practised magic, though they clearly saw the Sámi magic as distinct from their own, as indicated by terms such as Finnvitka, which refers specifically to the Sámi way of practising magic. It has however been observed that the descriptions of the practise of Norse magic – referred to as Seiðr – bear much resemblance to the descriptions and archaeological artefacts concerning Sámi magic, and it is likely that in an interconnected Arctic world, the two traditions of magic might develop shared features.

A woodcut from Olaus Magnus' Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus depicting three Sámi reindeer hunters on skiis with a hunting dog.

The medieval depictions of the Sámi were not always positive – and they were always tinged with a strong sense of otherness. Particularly when dealing with Sámi magic, Christian sources were prone to passing harsh judgement on the Sámi sorcerers and the Norsemen who courted them, however the appreciation of the Sámi as hunters, traders, and wizards without par is mostly positive throughout the corpus of Old Norse literature. However, in reality the Norse appreciation of the Sámi appears to have been ingenuine, appreciating the instrumental value of the trade-goods they could sell forward to Southern Europe or the magic they could provide. The conduct of Norse aristocrats regarding the Sámi shows serious signs of entitlement and oppression, which continue in many ways to present day.

A list of sources perused for this blog-post

- Aalto, S., "Alienness in Heimskringla: Special Emphasis on the Finnar", in Scandinavia and Christian Europe in the Middle Ages, Papers of the 12th International Saga Conference Bonn/Germany, 28th July-2nd August 2003, ed. R. Simek & J. Meurer (Bonn, 2003), 1-6

- Barraclough, E.R., "Arctic Frontiers: Rethinking Norse-Sámi Relations in the Old Norse Sagas", in Viator 48, (2017), 27-51

- Bately, J. & Englert, A., Ohthere's voyages : a late 9th-century account of voyages along the coasts of Norway and Denmark and its cultural context, (Roskilde, 2007)

- Hansen, L.I. & Olsen, B., Hunters in Transition: an outline of early Sámi history, (Leiden, 2013)

- Hofstra, T. & Samplonius, K., "Viking Expansion Northwards: Mediaeval Sources", in Arctic 48, (1995), 235-247

- Keller, C., "Furs, Fish and Ivory: Medieval Norsemen at the Arctic Fringe", in Journal of the North Atlantic 3, (2010), 1-23

- Pállson, H., "The Sámi People in Old Norse Literature", in Nordlit 5, (1999), 29-53

- Price, N., The Viking Way: Magic and Mind in Late Iron Age Scandinavia, (Oxford, 2002)