Go East, Young Man

2021-06-10

How the Viking Age Norse in Eastern Europe

- Came up with the idea to head East

- Changed their surroundings

- Adapted to the new environment

In my last post I discussed some elements of the Norse presence in Viking Age England. Today we’ll be turning our metaphorical globe clockwise, passing over continental Europe and Scandinavia itself, centring our attention on Eastern Europe, from the Baltic coast to the Black and Caspian Seas, and the wriggling network of rivers in between. During the Viking Age this region was one of the hotspots for Norse trading, raiding and settlement, though in contrast with Western Europe, we have far fewer contemporary written accounts, and what we have is less widely known.

Beginning in the eighth century, Norse merchants were drawn along Eastern Europe’s great riverways towards Central Asia and the Middle East. The Norse were attracted to the region by the spread of dirhams along the existing trade networks from the Abbasid caliphate, which spanned the Middle East and the Mediterranean coast from modern-day Iran to Portugal. The Abbasid dirhams were minted of high-quality silver, which the Norse greatly desired. The Viking Age Scandinavian economies were bullion economies – trade was carried out by weighing metal in coins to determine a rate of exchange for goods, rather than by the nominal value of the coin itself. Much of the coinage found in Norse Viking Age hoards is so called “hacksilver” – coins broken into smaller pieces; Norsemen would make change to pay for smaller purchases by physically cutting up their cash. Coins with a higher, purer content of precious metals, such as the Caliphate’s dirhams, were highly desirable to the Norse, as they were worth more in their economic system compared with coins of lower quality metal.

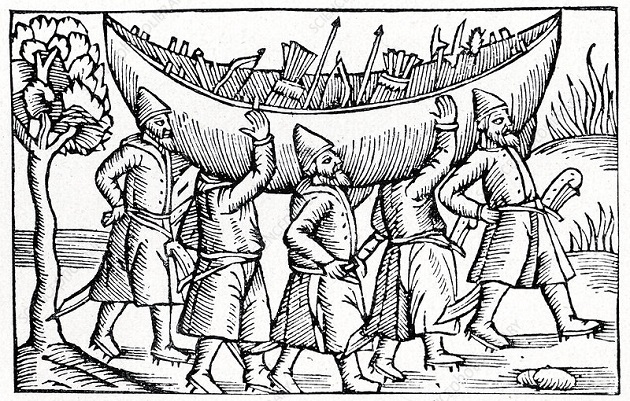

The Norse, a seafaring people, were able to make use of the waterways of Eastern Europe on their journeys to the Central Asian and Middle Eastern markets where they could exchange Northern trade goods for dirhams. Their main early markets were at Itil, the capital of Khazaria on the shore of the Caspian Sea, and Bolghar, the capital of the Volga Bulgars, in the present day Russian Republic of Tatarstan. To reach these markets Norse merchants travelled along the Volkhov, Daugava, Dvina, Oka, Don, Dnepr and Volga rivers. The distance being great and requiring portage – carrying boats from one river to another overland – at several locations, Norse settlements along the trade routes began to form.

Here we see some Norsemen portaging their boat, an activity required to reach Itil and Bolghar from the Baltic Sea. This woodcut is from the sixteenth century Swedish writer Olaus Magnus' A Description of the Northern Peoples.

The earliest Norse settlement in Eastern Europe is Staraja Ladoga, known as Aldeigjuborg in Old Norse sources, settled on the shore of Lake Ladoga in the 750’s. Staraja Ladoga was a mostly Norse settlement in lands inhabited by Baltic, Finnic, and Slavic peoples. Staraja Ladoga housed workshops for making crafts for trade, mainly metalworking and glass beads, as well as workshops for repairing ships. Compared to the long and risky journey to the Eastern markets, running a business at a stopping point along the trade route catering to those brave enough to make the journey was still profitable with a much lower risk. In the ninth century Rurikovo Gorodische was founded further downriver from Staraja Ladoga, as it was a more secure location with better farmlands. At this time new Norse settlements emerged along the various rivers of Eastern Europe, at Pskov, Beloozero, Jaroslavl, Rostov – many Russian cities you may have heard of, all originally founded by the Norse. Unlike Staraja Ladoga, these settlements housed comparatively smaller Norse populations in contrast with a larger non-Norse population. In these settlements the Norse formed a military elite, subjugating their neighbours and extorting them for goods to trade at the distant markets – mainly furs, amber, swords and slaves. The Norse were drawn further inland, toward the eventual heart of Kievan Rus’, the city of Kiev on the Dnepr river. These new settlements were very profitable for the Norse settlers, who enriched themselves on tributes from the neighbouring peoples and were able to amass merchandise for sale much easier and closer to the Eastern markets.

At this point it’s important to discuss the term Rus’. Rus’ is a term referring to the Norse settlers in Eastern Europe, who eventually formed their own culture and society largely separated from their Scandinavian origins. The word is the etymological root for Russia, and probably comes from the name the Finnic peoples living in Eastern Europe at the time (far further to the south and east than the boundaries of present-day Finland) gave to the Norse passing through their lands. Being a minority in the lands they were settling in, the Norse mingled with the local populations, having children of mixed Norse and Finnic, Baltic or Slavic parentage, living in communities where these cultures existed simultaneously, and exchanging elements of their cultures. Overtime from the eighth century, the culture of the Norse settlers gradually became a separate Rus’ culture. The physical description of the Rus’ given in a tenth century account by Ibn Fadlan, an Arab missionary and ambassador to the king of the Volga Bulgars, does not match archaeological records or descriptions of the Norse found elsewhere. Ibn Fadlan claims that the Rus’ were tattooed all over from their fingers to their necks, that the Rus’ women wore two brooches with knives attached to them, as well as torques – neck rings – reflecting the wealth of their husbands. These claims are not corroborated elsewhere and could therefore show changes in Rus’ material culture.

The customs of the Rus’ elites was also changing. In 839 some Rus’ envoys travelled to the court of Frankish king Louis the Pious with a Byzantine embassy, where they claimed to have been sent by their king, called chacanus, to establish friendly relations with the Franks. This encounter described in the Annals of St Bertin has generated much debate, as the word chacanus has been interpreted as a Latin translation of Khagan – a Turkic imperial title. Given the influence of the Khazar Khaganate, it is possible that the Rus’ elites had adopted the title for themselves. In the early tenth century the Rus’ began to develop their relations with Byzantium following a series of raids catching the Empire by surprise. The Rus’-Byzantine Treaties of 907, 911 and 944/5 established conditions for trade and territorial management. Rus’ served as mercenaries for the Byzantines as early as 874, with the Varangian Guard, the Byzantine Emperor’s elite force of Northern European mercenaries formerly established in 988. The ties to Byzantium contributed to the conversion of members of the Rus’ elite – in the 945 Rus’-Byzantine Treaty some of the Rus’ envoys swear by pagan gods, but a significant portion by the Christian god. While the most significant cultural influence impacting the Rus’ came from Byzantium, the Rus’ were also influenced by their Slavic neighbours. Sviatoslav, ruler of the Kievan Rus’ from 945 to 972, is described as having embraced the culture of the steppe nomads, waging war on horseback and adopting the hairstyle, habits, fashion as well as religion of the Slavs. Following Sviatoslav’s death, Vladimir the Great led the mass conversion of Kievan Rus’ in 987 to secure a military alliance with the Byzantine Emperor, as well as his sister’s hand in marriage. By the eleventh century the Rus’ were firmly a part of the Eastern cultural sphere of Europe, detached from their Scandinavian origins.

The Norse who set off for distant markets in the East were initially just merchants, but the long journey necessitated stops along the way, leading the Norse to settle down at opportune locations, founding settlements which initially served as rest-stops but with time grew into market-towns with farming and craft-industry. The further into Eastern Europe the Norse journeyed and the more they intermingled with the local populations, the more their culture developed into a separate Rus’ culture and identity.